Far-right groups are using Christmas carol rallies to promote exclusionary nationalism under the guise of faith. Bishop Lusa Nsenga-Ngoy calls for a clear Christian response: reclaiming Christmas as a story of welcome, diversity, and hope. London’s multicultural churches offer a powerful witness against fear-driven politics, reminding us that God’s love transcends borders and identities.

On Saturday 13 December, the “Unite the Kingdom” movement, led by far-right activist Tommy Robinson, plans a large outdoor carol rally in London under the slogan “Put Christ Back into Christmas.” What might look like a cheerful gathering of music and mince pies is, in reality, part of a broader political project. When Christian symbols and seasonal rituals are enlisted for a nationalist demonstration, the meaning of Christmas itself becomes contested terrain.

For many Christians, and anyone who cares about the health of our public square, this moment calls for a clear response—not a party-political intervention, but a defence of what Christmas has always proclaimed and what Christianity has always taught.

A Rally Isn’t Just a Rally

Robinson’s event is not a traditional celebration of Advent hope. It is a political spectacle: music, testimonies, flags, banners, and a deliberate attempt to fuse Christmas with a narrow sense of national identity. The message is not simply “Christmas,” but “our Christmas.” It trades on an exclusionary myth of cultural ownership, wrapping faith around a nostalgic ideal of God, nation, and heritage.

This is a familiar manoeuvre for far-right movements across the globe, which routinely appropriate Christian imagery to bolster their claims. At its heart lies a politics of fear: fear of change, fear of difference, fear of the imagined “outsider.” In such a framing, migrants, refugees, and religious minorities are transformed from neighbours into threats. But in the process, the gospel is distorted into something it has never been.

Why This Distorts the Heart of the Gospel

The Christmas story itself stands in quiet but decisive contradiction to this worldview. Theologically, Christmas is the story of God crossing borders, not protecting them. Jesus is born to a family navigating displacement. The first to greet him are shepherds whose work left them on the social margins. The next to honour him are travellers from distant lands.

From its beginning, the Christian story is not about guarding identity but welcoming difference. Scripture repeatedly insists that God’s love is expansive, boundary-breaking, and attentive to the vulnerable:

You shall welcome the stranger.

Perfect love casts out fear.

In Christ, there is no Jew or Gentile.

I was a stranger and you took me in.

To merge Christianity with ethnic or national identity is not simply unwise; it is a theological error. It reshapes faith into ideology and replaces grace with exclusion.

A Living Witness: London’s Multicultural Churches

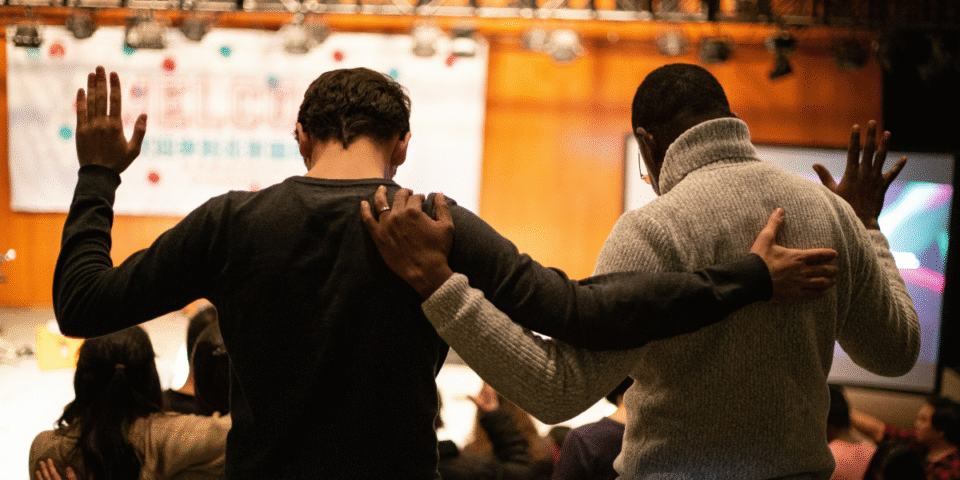

Against the backdrop of these attempts to weaponise Christian imagery, London’s churches offer a vivid counter-story, one that deserves far more attention. Across the capital, congregations gather each week that could not be further from the narratives of cultural purity or nostalgic nationalism. In churches from Hackney to Hounslow, from Southall to Stratford, the Body of Christ is embodied in ways that are joyfully, tangibly global. Worshippers come from every walk of life and from every corner of the world. Prayers rise in many accents and many languages. Harmony is created not by sameness but by shared faith expressed through different cultures.

These communities cultivate spaces of mutuality where we hear God’s story of love refracted through a multitude of voices. They model what the Church has said from its earliest days: that the gospel is not the possession of one tribe or nation, but a gift entrusted to a people drawn from every people. London’s churches, vibrant, diverse, interwoven, reveal a Christianity that is alive precisely because it is open.

If the far-right claims Christmas as the heritage of a narrow few, London’s congregations beautifully demonstrate the opposite: Christmas belongs to the world.

A Different Christian Witness

It is for these reasons that the Church of England and other Christian leaders have spoken out. Their recent poster campaign, stating “Christ has always been in Christmas” and “Outsiders welcome”, is not a political stunt, but a defence of the gospel’s integrity. It is a refusal to let the language of faith be captured by exclusionary movements.

At stake is nothing less than the central truth of Christianity: that God’s love extends beyond borders, identities, and fears.

Why This Matters Beyond the Church

This is not only a Christian concern. When cultural or religious traditions are claimed as the exclusive property of one group, the result is social fragmentation. Civic belonging becomes conditional. Pluralism begins to fray. Fear-driven politics divides neighbours and corrodes trust. Paradoxically, this was powerfully illustrated in the Christmas narrative through Herod’s anxious and brutal response.

Christmas has long functioned as one of the few shared seasons that bind us across difference. Allowing it to become a tool of exclusion harms us all.

What We Can Do

- Recognise the rhetoric. A slogan like “Put Christ Back into Christmas” sounds innocuous, but in the hands of a nationalist movement, it becomes a tool of division.

- Celebrate the deeper meaning of Christmas. It is a story of hospitality, vulnerability, and God’s solidarity with humanity in all its diversity.

- Amplify voices of welcome. Support the Church of England’s campaign and other public witnesses to inclusion.

- Refuse fear as the basis of civic life. Real challenges deserve real solutions, not scapegoating.

- Organise a global carol service. Following the example of the Diocese of Leicester, churches and civic groups can host multicultural carol services that showcase the global beauty of Christian worship, a powerful, joyful alternative to nationalist appropriations of the season.

The Christmas Worth Reclaiming

Christmas begins not with power but with vulnerability; not with fortress walls but with open doors. It is a story in which outsiders are welcomed first, and a child born in obscurity becomes hope for the world.

As London watches what unfolds on 13 December, we face a choice. Either Christmas becomes a badge of exclusion, or it remains what it has always been: a proclamation of God’s peace on earth, goodwill toward all.

If something needs reclaiming this year, it is not Christmas from secular culture, but Christmas from the politics of fear. If anything, the story of Christmas is about God claiming us all.