1. Opening Liturgy at St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster

Words of Welcome and Introduction

The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you.

And also with you.

Prayer

Teach us, O God,

to view our life here on earth as a pilgrim’s path to heaven.

May we lament over our failings as your people, to walk together as you have called us.

May we rejoice in all those who have shown us a better way.

And grant that as we journey on the Way of holiness, we may build a more racially just society, as companions along the road.

For the glory of your name. Amen.

Reading: Ephesians 2:14–16

For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility, by setting aside in his flesh the law with its commands and regulations. His purpose was to one new humanity out of the two, thus making peace, and in one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility. (NIV)

Prayer (Adapted from Pilgrim’s Way by Jenny Child)

You call us, Lord,

to leave familiar things and to leave our “comfort zone”.

May we open our eyes to new experiences,

may we open our ears to hear you speaking to us,

and may we open our hearts to your love.

Grant that this time spent on pilgrimage

may help us to see ourselves as we really are,

and may we strive to become the people you would have us be. Amen.

For each river that might impede,

be our safety, O Lord of life.

For each place where we might rest,

be our peace, O Lord of life.

For each sunrise and sunset,

be our joy, O Lord of life.

Reading: Revelation 7:9

After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people, and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb.

Prayer

Eternal God, give us the courage to set off on pilgrimage.

Sometimes our hearts will be heavy as we plod along,

and our feet will ache and feel dirty.

Other times we will rejoice as the sun shines on the path stretching before us.

May we ponder the truth,

that the pilgrim’s journey is never finished till they reach home.

Amen.

Blessing

May God the Father who created you, guide your footsteps.

May God the Son who redeemed you, share your journey.

May God the Holy Spirit who sanctifies Holy Spirit

be with you wherever you may go.

Amen.

In Silence on Your Own Before Beginning the Journey

- To start, choose an intention for the walk.

- Why are you choosing to set out on this journey?

- What intention will you carry in your heart each step along the way?

Request:

Your intention can be a form of petition requesting a special grace from God for yourself or on behalf of another. It could be for a spiritual, emotional, or physical healing.

Repentance:

You can walk a pilgrimage as a form of penance for yourself and the church, recognising and repenting of sin as you seek to renew your relationship with God.

Relationships:

A conversation you wish to have, a companion you wish to connect with on the walk.

Rejoicing:

You can also walk a pilgrimage in thanksgiving for blessings already received.

2. St Margaret’s Church, Westminster – Olaudah Equiano

Liturgy

Look on me and answer, Lord my God.

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

and my enemy will say, “I have overcome him,” and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

History

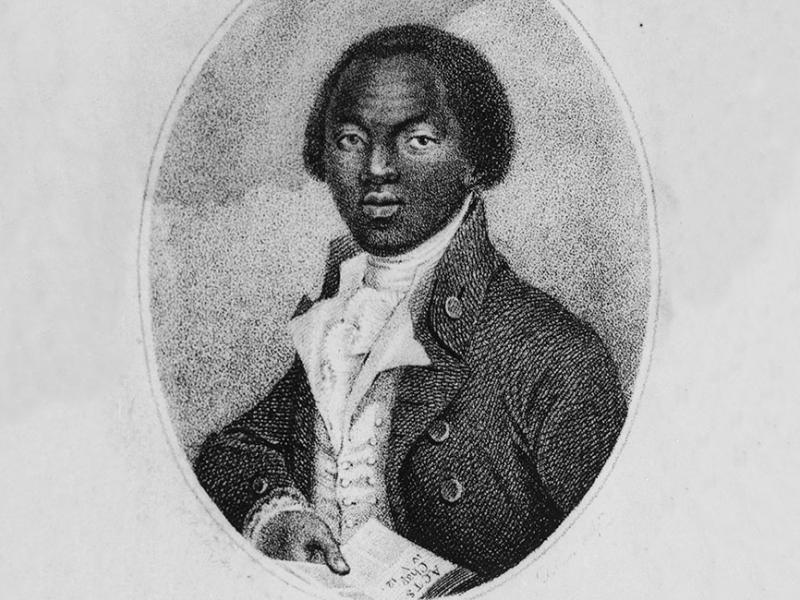

Olaudah Equiano arrived in London in the mid-1750s as the enslaved servant of British sea captain Michael Pascal. During his time in Westminster, he lived with Pascal’s cousins, the Guerin family, who introduced him to education and the Christian faith. Learning that baptism was essential for salvation, Olaudah asked the Guerin family to arrange the ceremony. In February 1759, he was baptised at St. Margaret’s Church under his enslaved name, Gustavus Vassa.

After purchasing his freedom in 1768, Equiano trained as a barber and returned to life at sea. By the 1780s, he became deeply involved with London’s abolitionist movement, joining forces with campaigners and helping to form the Sons of Africa—a group of free Black men who wrote to newspapers advocating for the end of slavery. In 1788, he published his autobiography to expose the brutal realities of enslavement, touring Britain to raise awareness and spark conversations about racial injustice.

Equiano passed away in 1797, a decade before the British Empire abolished the transatlantic slave trade. His legacy lives on in history books, but countless other Black Londoners remain absent from the record. May historians and activists continue to uncover and share these hidden stories.

Prayer

God of all, we confess that we have inherited a faith that was used to justify theft of native lands and the enslavement of your people.

From this sin, we ask for deliverance.

Forgive us for where we have failed to remember and understand, Lord, and in your mercy, set us free.

But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation.

I will sing the Lord’s praise, for he has been good to me.

3. King Charles Street, Westminster – Ignatius Sancho

Liturgy

Look on me and answer, Lord my God.

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

and my enemy will say, “I have overcome him,” and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

History

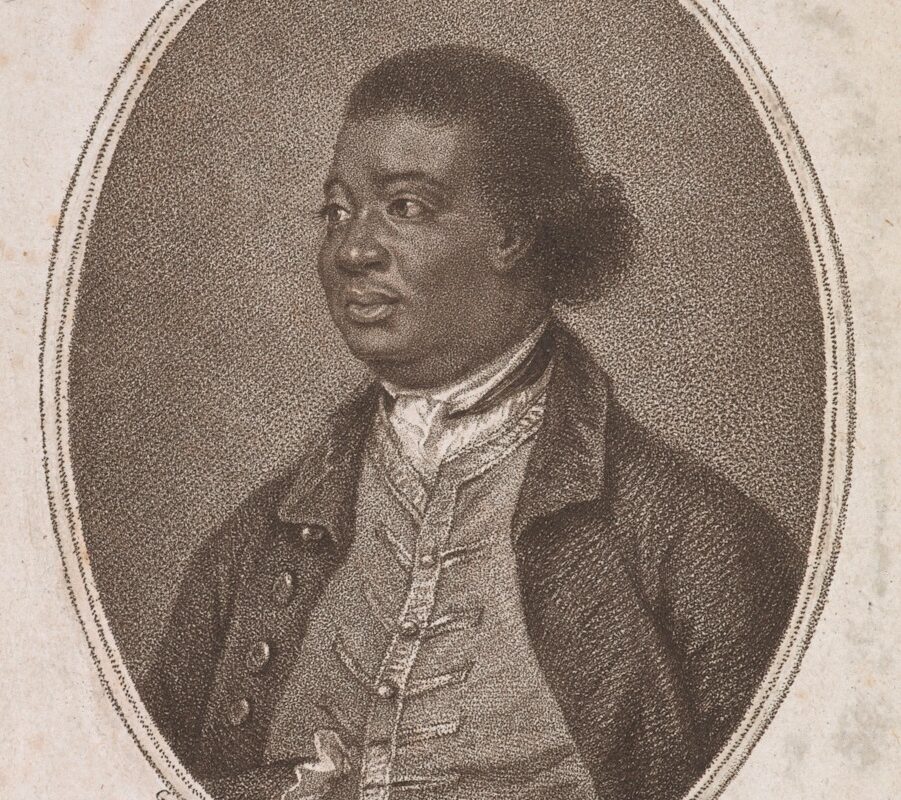

Ignatius Sancho was born into slavery aboard a transatlantic slave ship in 1729. As an infant in the early 1730s, he arrived in London and was raised in a household in Greenwich.

Over time, Ignatius gained the attention of the kind-hearted and influential Montagu family, who took him in. He served them intermittently until 1773.

Sancho married Anne Osborne, a fellow Black Caribbean woman, in December 1758 at St. Margaret’s Church in Westminster. Together, they had eight children, though sadly, many died in infancy. The family lived in the Westminster area, where Sancho became a well-known figure.

With the support of the Duke of Montagu, Sancho opened a grocery shop on King Charles Street in 1773. He was a highly educated man who corresponded with prominent individuals, advocating for the abolition of the slave trade through his eloquent letters.

Sancho also composed music, with several of his works published. Notably, he became the first known person of African descent to vote in British general elections, casting his ballot in 1774 and again in 1780.

While Sancho’s remarkable life has been preserved in history, countless other Black Londoners lived and struggled in obscurity. May historians and activists continue to uncover and share these hidden stories, ensuring their legacies are not forgotten.

Prayer

Touch hearts that have been shrivelled by generations of suppressed empathy,

and eyes that have lost the ability to see brothers and sisters who suffer from systemic injustice.

Forgive us for where we have failed to remember and understand, Lord,

and in your mercy, set us free.

But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation.

I will sing the Lord’s praise, for he has been good to me.

4. Schomberg House & St. James’ Piccadilly – Ottobah Cugoano

Liturgy

Look on me and answer, Lord my God.

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

and my enemy will say, “I have overcome him,” and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

History

Ottobah Cugoano arrived in London in 1772, brought by his enslaver, Alexander Campbell. A year later, on 20 August 1773, he was baptised at St James’ Church, Piccadilly, taking the Christian name John Stuart. Around this time, he appears to have gained his freedom, though he continued working as Campbell’s servant.

When Campbell returned to Grenada in 1778, Cugoano remained in London. By then, he had become literate and well-educated. By 1784, he was employed as a servant by Richard and Maria Cosway, a celebrated artistic couple who painted for George, Prince of Wales. They lived at Schomberg House on Pall Mall, near Buckingham Palace.

In 1786, Cugoano became actively involved in the political debates surrounding slavery and race in Britain. He joined the Sons of Africa, a group of Black abolitionists that included his friend Olaudah Equiano.

In 1787, Cugoano published his influential book, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species. More than a personal narrative, it was a powerful and principled critique of transatlantic slavery, grounded in Christian ethics and moral reasoning.

While Cugoano’s legacy has been reclaimed in historical records, countless other Black Londoners lived and contributed in silence. May historians and activists continue to uncover and share these hidden stories, ensuring their voices are heard.

Prayer (taken from: Black Liturgies by Cole A Riley)

God our maker,

We honour the sacred multitude that resides in you.

May the guardian in you protect us.

May the child in you delight in us.

May the friend in you challenge us.

May your ashes resurrect us.

May your sky shelter us.

May the mystery of you liberate us.

Provide abundance and healing in all forms to those who need it today,

And deliver us from shame, hatred, and the chains that bind us.

For you have made us—glory—and we are still being made. Amen

5. Cato Street – William Davidson – The site of his arrest

Liturgy

Look on me and answer, Lord my God.

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

and my enemy will say, “I have overcome him,” and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

History

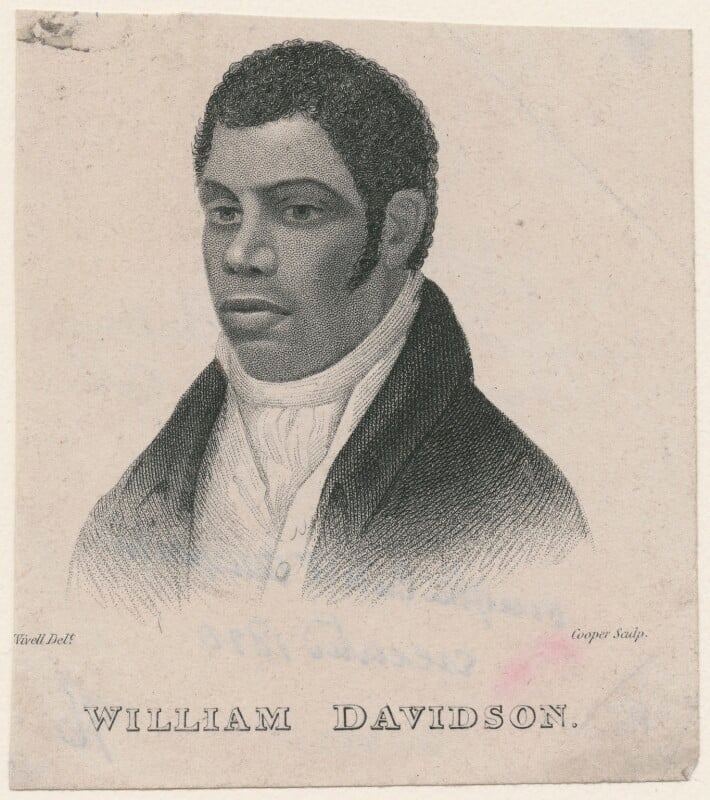

William Davidson was of mixed heritage — his father, a White English lawyer in Jamaica, and his mother, a free Black woman. Born in Kingston in 1786, Davidson was sent to Edinburgh, Scotland in 1800 to pursue his education. He explored careers in law and the navy before eventually settling as a furniture maker, a trade he continued when he moved to London in 1815, living with his family in Marylebone.

Davidson became deeply interested in social and political justice, joining the Marylebone Union Reading Society, where he engaged with radical ideas. It was there he met Arthur Thistlewood, a revolutionary who believed that violent uprising was the only path to justice for the poor. Davidson was persuaded by Thistlewood’s views and joined a group that met in February 1820 to plan a revolt. Unbeknownst to them, one member was a government informant. On the night of 23 February, police raided the meeting and arrested the conspirators.

At his trial for treason, Davidson made a powerful appeal against racial prejudice, stating:

“I hope the jury do not imagine that because I am a man of colour I am lacking in humanity.”

Despite his plea, Davidson and his fellow conspirators were convicted and executed by hanging on 1 May 1820.

Davidson’s life and activism have been reclaimed in historical records, but many other Black Londoners who fought for justice remain forgotten. May historians and activists continue to uncover and share these hidden stories, ensuring their voices are heard.

Prayer

Grant us courage to renounce the false teaching that we can somehow know you without being committed to justice for all people.

Forgive us for where we have failed to remember and understand, Lord, and in your mercy, set us free.

But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation.

I will sing the Lord’s praise, for he has been good to me.

6. Grand Union Canal – Lascars

Look on me and answer, Lord my God.

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

and my enemy will say, “I have overcome him,” and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

History

As we pause by the Grand Union Canal, we remember the thousands of Arabs, Asian, and Black sailors who worked tirelessly for the merchant ships of the British Empire during the huge expansion of trade and industry in the nineteenth century. They were known as lascars, and they took the lowest positions on the ships, including dangerous work with the ships’ boilers.

This canal carried industrial goods from Birmingham that would have been traded around the globe. From Paddington, the Regent’s Canal goes to Limehouse in the Docklands area of East London, where many of the lascars stayed when they were not at sea. The Strangers’ Home for Asiatic, Africans, and South Sea Islanders was opened in Limehouse in 1857 to support impoverished lascars and help them find new employment. The London City Mission was involved in the Strangers’ Homework.

Some lascars settled down in the East End, and their families became part of burgeoning multiracial communities in Britain.

Prayer

Grant us courage to renounce the false teaching that we can somehow know you without being committed to justice for all people.

Forgive us for where we have failed to remember and understand, Lord, and in your mercy, set us free.

But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation.

I will sing the Lord’s praise, for he has been good to me.

Statement Before Setting Off to Notting Hill

Cugoano, Equiano, Sancho, and Davidson call us to lament the racial injustices and horrors of the enslavement of Africans across the Atlantic. Yet we also rejoice that they were pioneering Black Britons whose lives and legacies continue to inspire.

Many men and women, including the lascars, followed in their footsteps long before the major migration of Caribbean people to Britain after the Second World War.

The second half of our pilgrimage takes us to Notting Hill, an area where many West Indian migrants settled into slum housing and sought work with employers who were willing to look beyond racial prejudice. By the end of the 1950s, Notting Hill had become a powder keg of racial tensions, stirred up by extreme right-wing political activists—most notably Sir Oswald Mosley. These tensions erupted into riots on the streets of Notting Hill at the close of the summer of 1958.

7. Southam Street – Kelso Cochrane – The site of his murder

Liturgy

Look on me and answer, Lord my God.

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

and my enemy will say, “I have overcome him,” and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

History

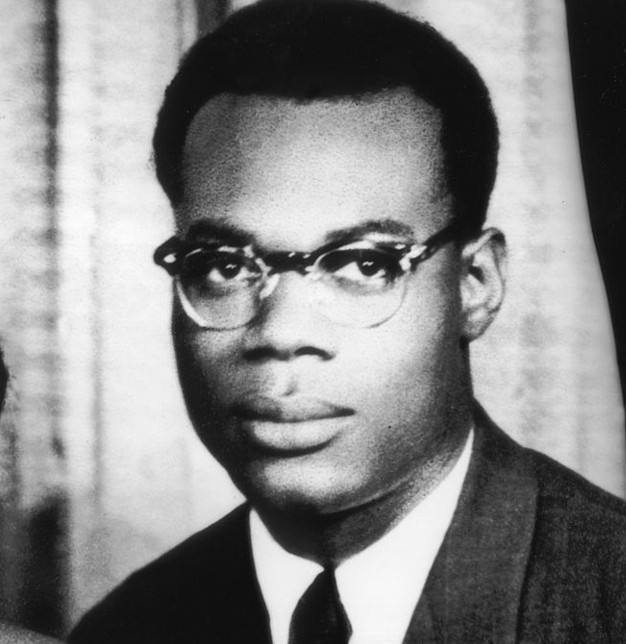

On 17th May 1959 came the awful climax of racial hatred in Notting Hill, when a 32-year-old carpenter from Antigua, Kelso Cochrane, walking home late at night from A&E at Paddington General Hospital, was stabbed in the heart on this street corner.

White youths were seen attacking a Black man by people nearby, and a taxi driver also witnessed part of the incident. The driver helped two Black men who were passing by to take Kelso to St. Charles’ Hospital, where he died a few hours later.

The police refused to recognise it as a racist attack, but the local communities knew different. The police were disinterested in the newcomers from the Caribbean, and many displayed the racial prejudices of those who were causing racial violence.

By contrast, over a thousand people—Black and White—turned out on the streets of Notting Hill near St. Michael and All Angels’ Church on Ladbroke Grove on 6th June 1959 for Kelso’s funeral. The police wanted his body taken back to the Caribbean to avoid attracting pilgrims, but Kelso is still buried in Kensal Green Cemetery to this day.

Prayer

In your mercy, help us mourn the divisions among the body of your Son, and work for healing in the places where we gather to worship you.

Forgive us for where we have failed to understand, Lord, and in your mercy, set us free.

But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation. I will sing the Lord’s praise, for he has been good to me.

8. Offices of the Worldwide Anglican Communion

We remain here for lunch, rest, and reflection.

Questions for Personal Reflection

• What has most encouraged me today?

• What has most challenged me today?

• How will the above affect my prayers?

• How will the above affect my actions?

• Name something specific you feel God calling you to do…

9. Tavistock Road, Ladbroke Grove – Claudia Jones & Rhaune Laslett

Blue Plaques remembering the joint ‘godmothers’ of the Notting Hill Carnival

Liturgy

Look on me and answer, Lord my God.

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

and my enemy will say, “I have overcome him,” and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

History

Claudia Jones was one of the organisers of a burial committee that raised funds for Kelso Cochrane’s funeral. A leading figure among London’s West Indian immigrants, she founded the West Indian Gazette newspaper and was deeply affected by the Notting Hill riots of the previous year. Determined to bring hope and unity to the community, she launched the Caribbean Carnival Committee in November 1958 to organise a cultural event that would highlight the positive contributions of West Indians to British society.

The first carnival was held indoors at St Pancras Town Hall in February, aligning with the timing of Caribbean carnivals. Claudia saw the event as more than entertainment—it was a political and cultural statement. Proceeds from the carnival’s souvenir brochure, titled “A people’s art is the genesis of their freedom,” were used to help pay fines for Black and White youths who had stood up for racial justice during the Notting Hill unrest.

These indoor carnivals later merged with a local Notting Hill Street fayre organised by Rhaune Laslett, a community activist who envisioned a multicultural celebration. Together, their efforts laid the foundation for what we now know as the Notting Hill Carnival.

Prayer

We pray with thanksgiving for the prophetic leaders who guide, challenge and inspire us today. Give us grace to follow them to freedom.

Forgive us for where we have failed to understand, Lord, and in your mercy, set us free.

But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation. I will sing the Lord’s praise, for he has been good to me.

10. Notting Hill Methodist Church – Revd Bruce Kenrick

Anti-Apartheid Conference – an example of intercultural action for social justice

Liturgy

Look on me and answer, Lord my God.

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

and my enemy will say, “I have overcome him,” and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

History

The Notting Hill Methodist Church was transformed in 1960 by a new approach to teamwork and social activism, rooted in the belief that Christian faith should make a practical difference to people’s lives—especially the poor.

Social activism flourished with the arrival of the Reverend Bruce Kenrick, who came down from Scotland to minister in the inner city. In 1962, he moved his family into a small, decaying house at 115 Blenheim Crescent. Alongside other activists, Kenrick founded the Notting Hill Housing Trust (NHHT). Their mission was to purchase properties, renovate them to a decent standard, and rent them at fair prices to those in need.

The NHHT raised substantial funds and, within five years, had become a major presence in West London, housing nearly 1,000 people. In 1969, the Trust moved its offices to All Saints Road—just down the street from the Caribbean-owned Mangrove restaurant—placing it at the heart of the community it aimed to serve.

Prayer

We pray that we may know the power of reconciliation.

Wherever there is division between us and others, because of our race or ethnicity,

we pray that we may all be led to reconciliation.

We pray for all who work to bring communities together in ways that are just and equal for all.

Lord, in your mercy, hear our prayer.

But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation.

I will sing the Lord’s praise, for he has been good to me.

11. Grenfell Tower – Khadija Saye and 71 other residents

A place of remembrance

Liturgy

Look on me and answer, Lord my God.

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

and my enemy will say, “I have overcome him,” and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

History

Khadija Saye attended the University for the Creative Arts at Farnham and earned a degree in photography. She lived with her mother, Mary Mendy, on the 20th floor of Grenfell Tower. Mentored by artist Nicola Green and connected to Tottenham MP David Lammy, Khadija explored her Gambian British identity through her art, which was exhibited at the Diaspora Pavilion during the 2017 Venice Biennale.

On 14 June 2017, Khadija and her mother died in the Grenfell Tower fire. The blaze began due to an electrical fault in a refrigerator on the fourth floor and spread rapidly up the building’s exterior. The fire was intensified by dangerously combustible cladding that had been added to the building’s façade. It burned for 60 hours.

Seventy-two people died, including two who later succumbed to injuries in hospital. It was the deadliest UK residential fire since World War II. For years, residents had raised concerns about safety, but these were ignored. Many of the victims were recent migrants and people of colour, and the tragedy exposed how their lives were undervalued in the face of cost-cutting and neglect.

Prayer

As we pray for reconciliation, we pray also for restoration.

We pray for those whose spirits and communities have been weighed down by racism.

Guide us as we strive to ensure everyone has equal dignity.

Lord, in your mercy, hear our prayer.

But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation.

I will sing the Lord’s praise, for he has been good to me.

12. St Clements Church – Act of Commitment

Dear people of God, we stand in the shadow of the prophets crying out for justice and peace. God calls us to be a people of reconciliation, serving a world in need. Courageous women and men have taken the risk of standing up and speaking out for the least and the lowest. This work involves risking ourselves for the sake of God’s love and moving beyond ourselves to seek and serve Christ and one another. We are all called to the work and ministry of social justice and reconciliation.

Therefore…

- Will you persevere in prayer and fellowship?

With the help of God, I will. - Will you proclaim the good news of reconciliation in both word and deed?

With the help of God, I will. - Will you acknowledge and address the prejudices that keep you from loving all God’s children?

With the help of God, I will. - Will you strive to see Christ in all persons, and value those with whom you disagree?

With the help of God, I will. - Will you seek to mend what is broken by human sin and greed?

With the help of God, I will. - Will you speak words that liberate and heal and break the bonds of silence?

With the help of God, I will. - Will you seek the perfect love which casts out all fear?

With the help of God, I will. - Will you work toward dismantling the sin of abuse of power?

With the help of God, I will.

Blessing

May almighty God empower you to continue his work of reconciliation,

give you the courage to overcome fears and embody love,

give you grace to grow in self-awareness and personal integrity,

and strengthen you to seek the unity that is in Christ,

that we may rejoice with all God’s children as disciples of God’s Son.

And the blessing of God almighty, the Father….. Amen.

Thank you for your participation in this pilgrimage and we continue in our prayers and work for racial justice.

The Diocese of London: Our Commitment to Anti-Racism

The Diocese of London is committed to being actively anti-racist. We have a significant role to play in combating racism within our structures, systems, and people to build a better future for all.

Racism and other forms of discrimination are wholly incompatible with:

- Jesus’ command: “Love one another” (John 15:12)

- His promise: “Life in all its fullness” (John 10:10)

- Our diocesan vision for justice, dignity, and inclusion.